From space to harsh, unforgiving earth

by Serge Kaganski

Wednesday, October 17th

POSTED ON OCTOBER 18, 2018

I could not attend the exceptional projection of “2001: A Space Odyssey” in 70mm at the Auditorium of Lyon, or the presentation of Douglas Trumbull, special effects maestro of the film.

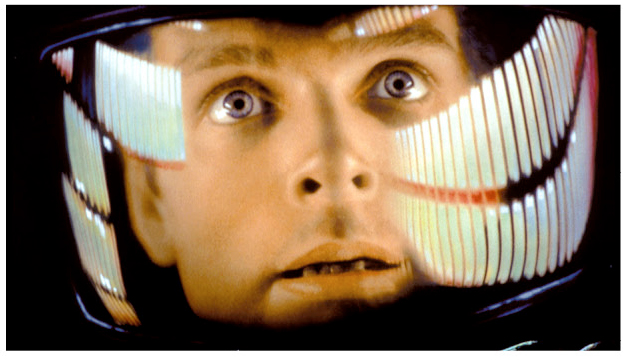

It is probably not a big deal. I have seen “2001” more than ten times (I’ve lost count), at least twice in 70mm. The first time was the most memorable: it was at the Kinopanorama, a now-defunct Paris movie theater in the 15th arrondissement, whose screen was so wide, it curved on the sides. My mother had taken me, I was 11 or 12 years old; space fascinated me like all kids and I loved the Odyssey of Ulysses. The film also fascinated me - “fascinated” is too weak a word - even if I did not understand anything about the last part, in the Louis XVI bedroom. A dozen views and a few decades later, I am still not sure I understand everything, but at least I have some keys to scientific, metaphysical and symbolic interpretation. What I also understand is that “2001” is a unique film in that it is both a popular worldwide hit, a historic cinematic milestone, seen it or not, everyone has heard of it, also, it is an experimental film that followed none of the rules (no narrative, almost no dialogue, long contemplative and poetic scenes that have no dramatic utility, the strange ending...). It is also a film that does not age because it asks questions that will remain unanswered for a long time, like, where does humanity come from? How and why does it evolve? Where is it going? And are we alone in the infinite cosmos? “2001” allows you to dream about these questions and fantasize about possible and uncertain answers. Thank you again, Stanley Kubrick and Douglas Trumbull, for this timeless object of fascination.

Far from my stellar daydreams of “2001,” I went to introduce “Bicycle Thieves” at Pathé Bellecour, a film that takes us crashing back to earth and its harsh realities. The big theater was full, which is nice, with whole rows of middle school students, which is even more fun. De Sica's classic (which Liv Ullmann urged me to worship at Monday's dinner) is about the working-class, precariousness, unemployment, suffering, hopelessness and the shame of being poor. So many themes that resonate strongly in 2018. The more I see great heritage films at Lumière, the more I realize their permanent relevance, their eternal contemporaneity: if big films become dated by some secondary stylistic detail (wardrobe, decoration, cars, manner of speaking...), their attention to certain fundamental and universal aspects of the human experience guarantees their conjugation to the perpetual present.

I then continued my exploration of Henri Decoin, discovering “Not Guilty,” led by the immense Michel Simon, an actor in the vein of greatness of a Jouvet or Raimu, seen in in other Decoin films at Lumière. Another rough return to earth and its darkness. The scenario devices of “Not Guilty” are devilishly clever: an embittered provincial doctor is considering becoming a crime maestro, a genius killer, a virtuoso murderer; then he dreams of dying, leaving behind a legacy as a hyper-intelligent champion of Evil. But he is so good at not getting caught and leaving no sign of guilt, that no one suspects him. Worse, when he confesses his crimes, no one believes him, insisting that he is too much of a straight-laced simpleton to be capable of such Machiavellianism. In spite of his sophisticated murderous elaborations, the man will die in anonymity, a small unremarkable country man, the most hateful outcome possible… This terror of being anonymous and misunderstood probably inhabits most artists. The rather insane scenario evokes Lars von Trier's latest film,” The House That Jack Built”, by pairing art and crime. Despite all these qualities, I would place this Decoin a little below the others, perhaps precisely because it is a bit too neat in its scenario devices. Nevertheless, this film with its two possible endings (both were screened, like for “Monelle”), has won public acclaim.

That evening, I introduced Arthur Penn's “The Chase” at the IRIS in Francheville, one of the theaters in the outer suburbs that participates in the festival. What a pleasure to discover a section of the western outskirts, where non-Lyonnais rarely venture, with a superb municipal cultural structure, an attentive and curious public. Access to culture should involve all areas of a territory, not just the privileged downtowns, and the Lumière festival works hard at this, because Thierry Frémaux's concern has always been to fight cultural inequalities. Finally, how gratifying to introduce a powerful film, punishing, violent, of a wild beauty, another pitiless return to our terrestrial depravity, a film which stars the 2018 Lumière Award recipient, Jane Fonda. The ruthless pursuit is perhaps not her most prominent role (she excels, but is more memorable in “Klute,” “Coming Home,” or “Barbarella”), but it is certainly one of her best films. And what it shows about life on earth (racism, violence, brutality, bowing to base impulses), makes you want to return to Jupiter with HAL 9000 and astronaut Bowman.